The morning that Russia invaded Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin appeared on Russian television outlining his rationale for war. While concern for what was about to befall Ukrainians and Ukraine dominated many peoples’ minds, politicians and scholars alike were left scratching their heads at Putin’s stated justifications. Well-worn concerns about NATO expansion and Western influence were part of his offered rationale, but so too were humanitarian concerns—specifically, Russia’s need to combat far-right nationalism and neo-Nazi extremism in Ukraine and to stop Ukraine’s genocide of ethnic Russians. The former are well known central strategic concerns for Russia, the latter are products of a long-term disinformation and misinformation campaign by the Russian government. It is worth saying outright: there is no evidence of any kind of Ukrainian genocide against ethnic Russians. Nevertheless, Putin claimed:

We had to stop that atrocity, that genocide of the millions of people who live there and who pinned their hopes on Russia…the leading NATO countries are supporting the far-right nationalists and neo-Nazis in Ukraine…The purpose of this operation is to protect people who, for eight years now, have been facing humiliation and genocide perpetrated by the Kiev [Kyiv] regime. To this end, we will seek to demilitarise and denazify Ukraine….I would also like to address the military personnel of the Ukrainian Armed Forces…Your fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers did not fight the Nazi occupiers and did not defend our common Motherland to allow today’s neo-Nazis to seize power in Ukraine…1

Over the past several months, as the world observed Russian military exercises and buildup near the Ukrainian border, worries of a Russian invasion became increasingly widespread. While Putin has positioned the invasion as a response to recent events, he and other Russian officials planted the seeds years ago, preparing the narrative, rhetoric, and ultimately the rationale for invasion. As early as 2008, Russian diplomatic statements claimed growing Ukrainian far-right extremism and fascism and expressed the need to denazify Ukraine and address alleged human rights abuses against Russian-speaking ethnic groups.2 This was years before the Euro-Maidan protests decisively aligned Ukraine with the EU rather than Russia. Putin’s rationale for invading Ukraine has been simmering for years.

Sound Familiar?

These types of justifications are not new to Russia—officials made similar accusations and claims before and during Russia’s military operations in the Russo-Georgian War of 2008.3 At the time, Russia accused Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili’s regime of committing atrocity crimes, and claimed to be intervening to save lives, prevent genocide, and protect Russian citizens living in Georgia. There was, however, no evidence of any genocidal activity by the Georgian government in the run up to Russia’s invasion. Further, while sadly 228 civilians from Georgia were killed during the five-day conflict, there was no evidence that the Georgian forces sought to deliberately target them.4 Additional casualties of this conflict included 170 service members and 14 police officers from Georgia, and 67 Russian service members.5

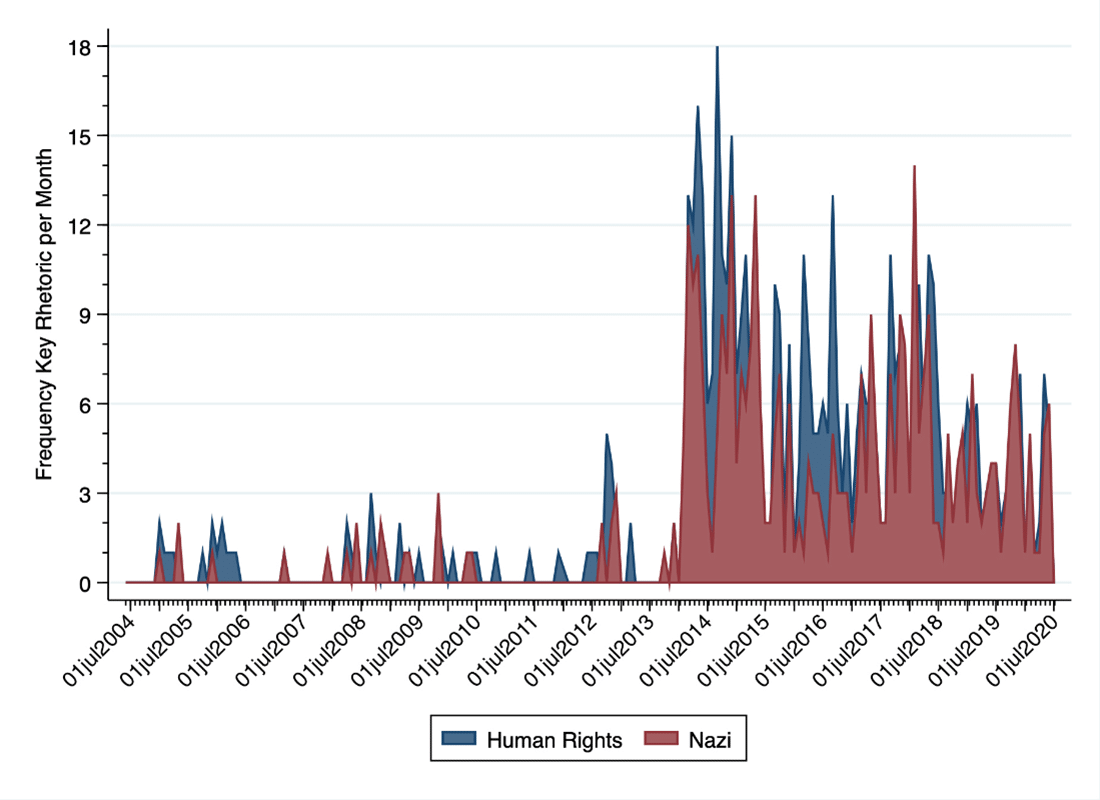

The FOCUSdata Project enabled us to conduct an in-depth 16-year analysis of official Russian rhetoric and strategic narrative building.6 FOCUSdata Project collected and analyzed 20,000 statements, press releases, and communiques from 2004-2020 that were disseminated in English by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.7 These English language documents were intended for global consumption and for building an international narrative. In this database, 2,947 of the statements specifically focus on Ukraine. Each posting contains multiple themes or narratives, but our research identified key themes in Russia’s rhetoric that became central to its justification for invading Ukraine. For example, nearly 18 percent of these statements concern alleged human rights violations, and approximately 13 percent condemn Ukraine and the West for supporting, or at least allowing, neo-Nazi extremism. Over 5 percent of these postings discuss both neo-Nazi threats and human rights violations. While many have balked at Putin’s recent claims and exaggerations about what has been occurring in Ukraine, the 16-year paper trail shows that key elements of Russia’s strategic narrative, while false, are central to this war.

Figure 1 shows the frequency of references to Nazism in statements referencing Ukraine. The early postings are generally related to references made in commemorative events celebrating the defeat of Nazis in World War II, while later statements increasingly refer to the alleged rebirth of fascism in Ukraine. The latter claims periodically surfaced in Russian rhetoric leading up to the beginning of the Euro-Maidan protests in November 2013, with a notable absence from 2010 to mid-2012. In 2008, Russia accused Ukraine of having Nazi sympathies because the country commemorated anniversaries of Ukrainian units fighting for Nazi Germany in World War II. For example, in June 2008 Russia denounced the Ukrainian celebration of the 65th anniversary of the SS Galicia Division.8 The following year, it expressed concerns regarding the commemoration of the 67th anniversary of the nationalist Ukrainian Insurgent Army—as well as of undue glorification other Ukrainian WWII groups with perceived far-right leanings.9

During the Euro-Maidan protests in 2013, Russia blamed much of the violence on far-right Ukrainian extremists, and blamed the West for the emergence of extremism in Ukraine.10 From then on, accusing Ukraine of being a state led/controlled by neo-Nazis became a standard Russian narrative. Russia accused neo-Nazis of instigating protests and placed the responsibility on them for the outbreak of armed conflict in south-east Ukraine. The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs continued to blame neo-Nazis and Ukrainian extremists for violence as the armed conflict simmered post 2014.11 These accusations declined over time, only to resurface in Russia’s rationale for invading Ukraine in 2022. Importantly, while such claims of the rebirth of fascism in Ukraine have been widely discredited abroad, they have been widely accepted in Russia where they have been heavily popularized by the ubiquitous Kremlin-controlled media.12

Key Russian Rhetoric About Ukraine

Figure 1. FOCUSdata Project, Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs Statements About Ukraine

Figure 1. FOCUSdata Project, Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs Statements About Ukraine

Accusations that Ukraine is violating the human rights of its residents (especially, ethnic Russians) follow a similar pattern to claims about neo-Nazism. While being made sporadically prior to the Euro-Maidan protests, they became a standard narrative with the onset of armed conflict in southeast Ukraine in 2014. In fact, frequently the references to the rise of Nazism are closely linked with claims of increased violence and human rights violations. For example, one statement from September 2014 describes the perceived human rights violations in Ukraine as entailing “massive deaths of civilians” due to “the growing spread of the radical, primarily ultranationalist, neo-Nazi ideology.”13 Following the fighting of 2014, Russia routinely accused Ukraine of aggression and various violations of international law. Interestingly, Russia did not accuse Ukraine of either planning or perpetrating genocide until the immediate lead up to the 2022 attack. This mirrors what Russia did with the 2008 invasion of Georgia, in which Russia initially provided accusations of grave human rights violations followed by accusations of genocide at the onset of the invasion.

A Broader Strategy

Russia’s finger-pointing at other countries’ human rights violations is standard operating procedure and not exclusive to their narrative demonizing Ukraine. For example, Russia routinely deflects criticism of its human rights record, as well as its press and internet censorship, by criticizing its adversaries’ human rights practices, in particular Ukraine’s and Georgia’s.14

When analyzing Russian diplomatic language, we should not overlook the role of information warfare, as Russia has a history of deception, disinformation, and propaganda. During the Cold War, Russians spread fake news and even forged U.S. government documents in an attempt to discredit the United States. More recently, the contemporary Russian Information Security Doctrine has called for information aggression against Russia’s geopolitical opponents— the West and specifically members of NATO. During the Cold War, the West placed much emphasis on identifying and countering the Soviet Union’s propaganda. A similar approach may be helpful with countering current propaganda and Russian rhetoric by ensuring that Russian statements on Ukraine and beyond are not reported as objective facts in the media. The Biden administration has succeeded at this during the build up to the invasion in its early days, adopting a strategy of pre-empting dis- and mis-information by publicly disclosing Russian narratives before they can propagate.

Our research suggests that the world should pay particular attention if Russia raises concerns that far-right extremism, Nazi sympathies, or human rights abuses are present in neighboring countries. Russia appears to be playing a long-term, strategic game by laying the groundwork for potential future interventions, creating narratives that later could be centerpieces of its rationale for war. Information has long been recognized as a critical foreign policy tool and now disinformation and misinformation campaigns need to be given the same weight and gravitas in international relations and foreign policy. The Russia-Ukraine war is the most recent and loudest example of how misinformation campaigns can be long-term strategic endeavors. With this war, a false narrative ten years in the making became the rationale for kinetic military actions and invasion.

—Juris Pupcenoks and Graig R. Klein

Juris Pupcenoks is a member of the Carnegie New Leader's program and an Associate Professor of Political Science at Marist College in New York. His research focuses on Russian strategic narratives, humanitarian intervention, threat perception, diasporas, and ethnic politics. His website is: https://sites.google.com/site/jurispupcenoks/home.

Graig R. Klein is an assistant professor at the Institute of Security and Global Affairs at Leiden University. His research explores the instrumentality of political violence, primarily terrorism and protests, and how dissident-government interactions inform tactical and strategic evolution in conflict processes, international security, and national security. In addition to his faculty position, he has served as an Academic Primary Investigator at the World Bank. For more information, please visit his website (www.GraigKlein.com) or follow him on Twitter (@graigklein).

- 1 Bloomberg News. “Transcript: Vladimir Putin’s Televised Address on Ukraine.” February 24, 2022. ↩

- 2 The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, “Russian MFA Spokesman Mihkail Kamynin Interview with RIA Novosti Regarding the Working Visit to Russia of Ukraine’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Volodymyr Ogryzko,” April 11, 2008, Available at: https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1693364/; The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, “Russian MFA Information and Press Department Commentary in Connection with the Message from Alexander Volkov, Head of the Russian Community of the Ivano-Frankovsk Region, Ukraine, to President of the Russian Federation Dmitry Medvedev,” June 23, 2008, Available at: https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1729715/. ↩

- 3 Juris Pupcenoks and Eric James Seltzer, “Russian Strategic Narratives on R2P in the ‘Near Abroad,’” Nationalities Papers 49, no. 4 (2021), pp. 757–75, doi:10.1017/nps.2020.54. ↩

- 4 CNN, “2008 Georgia Russia Conflict Fast Facts,” Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2014/03/13/world/europe/2008-georgia-russia-conflict/index.html. ↩

- 5 CNN, “2008 Georgia Russia Conflict Fast Facts,” Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2014/03/13/world/europe/2008-georgia-russia-conflict/index.html. ↩

- 6 Scott Fisher, Graig R Klein, Juste Codjo, “Focusdata: Foreign Policy through Language and Sentiment,” Foreign Policy Analysis, Volume 18, Issue 2 (April 2022),pp. 1-15, https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/orac002. ↩

- 7 Fisher, S. and G. Klein. 2020. Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1st Edition) [data file]. ↩

- 8 The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, “Russian MFA Information and Press Department Commentary in Connection with the Message from Alexander Volkov, Head of the Russian Community of the Ivano-Frankovsk Region, Ukraine, to President of the Russian Federation Dmitry Medvedev,” June 23, 2008, Available at: https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1729715/. ↩

- 9 The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, “Russian MFA Information and Press Department Comment on the Publication of Viktor Yushchenko’s Decree on Additional Measures for Recognition of the Ukrainian Liberation Movement of the 20th Century,” November 25, 2009, Available at: https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1628375/. ↩

- 10 For example, see The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, “Answer by the Russian Foreign Minister, Sergey Lavrov, to the question about the situation in Ukraine, during the joint press conference summarizing the results of the third session of the Russia-CCASG strategic dialogue at ministerial level, Kuwait City, 19 February 2014,” February 19, 2014, Available at: https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1668301/. ↩

- 11 For example, see The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, “Statement by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs regarding the events in Ukraine,” February 24, 2021, Available at: https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1670994/. ↩

- 12 Gaufman, Elizaveta. Security Threats and Public Perception: Digital Russia and the Ukraine Crisis.” Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. ↩

- 13 The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, “UN Conference on violations of human rights in Ukraine,” September 11, 2014, Available at: https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1647579/. ↩

- 14 S. Fisher, “Testing the Importance of Information Control: How Does Russia React When Pressured in the Information Environment?,” Journal of Information Warfare, vol. 18, no. 1 (2019), pp. 23–38, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26894655. ↩