What comes to mind when we hear the word “drone”? For many of us, it is the image of a General Atomics MQ-1B Predator drone launching a Hellfire missile at a suspected militant target. But is this picture beginning to change? Should this picture change?

As technology and innovation advance, some see a more benevolent side to drones. For instance, the “PARS lifeguard,” designed by Amin Rigi of RTS Lab in Iran (now London-based), is an octocopter drone that drops off lifesaving tubes that can reach a drowning victim four times faster than a lifeguard. Similarly, the “ambulance drone,” developed by graduate student Alec Momont at TU Delft, Netherlands, is an autonomous quadcopter drone that carries a defibrillator for patients in cardiac arrest with a webcam link to an emergency operator to give instructions. And in February 2015 the United Arab Emirates awarded a $1 million prize in its “drones for good” competition to the “Gimball” collisiontolerant drone, designed by the Swiss based Flyability, which has the ability to enter burning buildings through an opening as small as one foot and can provide a live video-feed assessment to locate victims.

Innovative drones such as these can provide many benefits. But there are important tensions associated with drone technology, even in their humanitarian uses. While scholars and the public alike have focused on the controversial CIA targeted killing programs in Yemen and Pakistan, “humanitarian drones” have quietly made their way into the hands of practitioners globally. At the same time, discussion of humanitarian drones has been largely eclipsed by the immense legal and ethical dilemmas that armed drones present. Nonetheless, the groundbreaking work of Kristin Bergtora Sandvik and Kjersti Lohne of the Peace Research Institute, Oslo, has paved the way for an emerging small body of literature on humanitarian drones (which as of yet tends to focus on issues of peacekeeping).

Drones come in a great many shapes, sizes, and capacities. Depending on their specific applications, they are known as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), unmanned vehicle systems (UVSs), and unmanned aerial systems (UASs). Whatever one prefers to call them, their growing presence in endless aspects of life—commercial delivery, policing, environmental monitoring, anti-poaching efforts, and aid delivery, to name only a few—indicates that drones are undeniably here to stay. UAVs are truly multipurpose machines, meaning their humanitarian attributes largely depend on who is using them and in what manner. I take “humanitarian assistance” to mean aid and actions designed to save lives, alleviate suffering, and protect and maintain human dignity. This assistance can occur both during and in the aftermath of man-made crises and natural disasters, and also be oriented toward strengthening preparedness for such situations. Humanitarian drones are unarmed UAVs utilized by organizations—and potentially states—that actively and consistently pursue such ends.

Full essay available to subscribers only. Access the essay here.

More in this issue

Summer 2016 (30.2) • Essay

Patti Tamara Lenard Replies

Is the revocation of citizenship—a policy increasingly adopted by democratic states—a violation of democratic principles? In an article published in the Spring 2016 issue ...

Summer 2016 (30.2) • Essay

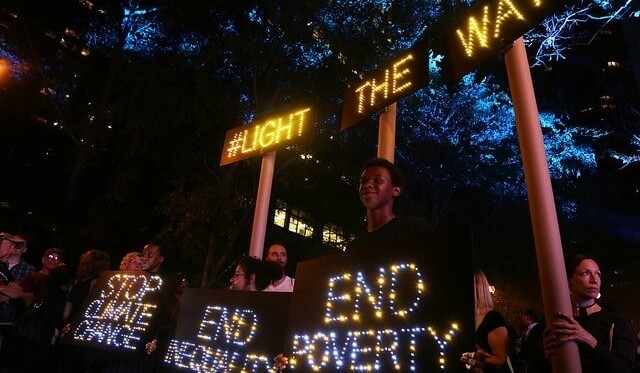

Equality as a Global Goal

The MDGs were often criticized for having a “blind spot” with regard to inequality and social injustice. Worse, they may even have contributed to entrenched ...

Summer 2016 (30.2) • Essay

When Democracies Denationalize: The Epistemological Case against Revoking Citizenship

Discomfort with denationalization spans both proceduralist and consequentialist objections. I augment Patti Lenard’s arguments against denationalization with an epistemological argument. What makes denationalization problematic ...