The global refugee regime encompasses the rules, norms, principles, and decision-making procedures that govern states’ responses to refugees. It comprises a set of norms, primarily those entrenched in the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, which defines who is a refugee and the rights to which such people are entitled. It also comprises an international organization, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which has supervisory responsibility for ensuring that states meet their obligations toward refugees.[1. Gil Loescher, The UNHCR and World Politics: A Perilous Path (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001); and Alexander Betts, Gil Loescher, and James Milner, UNHCR: The Politics and Practice of Refugee Protection (Abingdon, U.K.: Routledge, 2012).]

The underlying ethos of the refugee regime is a reciprocal commitment to the principle of nonrefoulement, that is, the obligation not to return a person to a country where she faces a well-founded fear of persecution. As the preamble to the 1951 Convention makes clear, the premise of the refugee regime is international cooperation; specifically, that states reciprocally commit to provide protection to refugees. The regime comprises two sets of obligations: asylum and burden-sharing. Asylum can be defined as the obligation that states have toward refugees who reach their territory; burden-sharing represents the obligation that states have toward refugees in the territory of other states, whether to financially support them or to resettle some of them on their own territory. The existing regime has a strongly institutionalized norm of asylum that is widely accepted; however, the norms related to burden-sharing are weak and largely discretionary.[2. Alexander Betts, Protection by Persuasion: International Cooperation in the Refugee Regime (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009).]

Political theorists have long debated the obligations that states have in relation to international migration. Broadly speaking, most political theorists recognize a special right to refugee protection, although the extent of this right is understood differently among communitarians and liberal theorists. Despite this apparent consensus, however, the existing refugee regime is at a crossroads. In the context of the Syria crisis, and with more people displaced today than at any time since the Second World War, the existing refugee regime is being challenged by the record number of people seeking protection. As a result, an increasing number of governments are closing their borders. Jordan, Hungary, Croatia, Kenya, Thailand, and Australia have all recently shut their borders to refugees, at least temporarily, suggesting that states’ commitment to asylum may be increasingly conditional. Furthermore, there are now new drivers of cross-border displacement, including climate change, food and water insecurity, and state fragility. Within this context, a set of normative questions arises—questions that have not drawn sufficient attention until now. The purpose of this essay, then, is to guide reflection on the obligations that states have today, both individually and collectively, toward refugees. Its intention is not to provide definitive answers, but rather to pose questions to further the normative debate.

WHY PROTECT?

Where does normative obligation come from? On what basis can we ground a claim to asylum? This has rarely been explored with respect to refugees. Yet today, when publics and electorates in Europe, Australia, and many other locations around the globe are asking why they should assist asylum seekers, it is important to identify the ethical grounds for that commitment. It is also important, however, to recognize that there can be a diverse set of reasons to normatively commit to refugee protection, including obligation, interests, and values.

Obligation

Refugee processing center, Kos, Greece. (Courtesy: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies/Creative Commons)

Refugee processing center, Kos, Greece. (Courtesy: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies/Creative Commons)

Most moral philosophers recognize that we have ethical commitments to others. The humanitarian principle implies that we have particular obligations toward those in need. There are a range of perspectives that can be advanced to support this thesis. At one end of the spectrum, communitarians suggest that our primary obligations are toward those within our own society. Yet even those like Michael Walzer, who assert that the state is analogous to a club, a neighborhood, or a family, recognize that refugees possess a set of moral claims on our political communities.[3. Michael Walzer, Spheres of Justice: A Defense of Pluralism and Equality (New York: Basic Books, 1983).] This is because they flee such desperate situations, and are in such dire need, that we should admit them to our territory insofar as the cost to our own societies is low. This obligation, therefore, is conditional. Fleshing this out, for instance, Garrett Hardin uses the metaphor of “lifeboat ethics,” highlighting that the carrying capacity of the state depends upon its ability to help refugees without causing great detriment to those already in the metaphorical boat.[4. Gerrett Hardin, “Lifeboat Ethics: The Case against Helping the Poor,” Psychology Today 8, no. 4 (1974).]

Alternatively, a range of liberal theorists argue that the threshold of “low cost” can be set much higher. Some liberals, drawing on Rawls, suggest that, behind the “veil of ignorance,” we are all potentially refugees, and that refugees are ordinary people in exceptional situations.[5. John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (New York: Belknap, 1974).] Hence our common humanity should be the basis of recognizing our moral obligation. For other liberal theorists, such as Joseph Carens, the rights of migrants, including refugees, can be grounded in basic democratic values of freedom and equality. He argues that this should entail “reasonable accommodation” of people’s differences.[6. Joseph Carens, The Ethics of Immigration (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 64.] At the extreme end of the spectrum, radical utilitarians such as Singer argue that ultimately it is morally untenable not to reallocate opportunities to poor people up to the point at which marginal utilities are equalized across all people. In other words, we should be admitting people right up until their quality of life is no worse than our own.

Attempting to reconcile this spectrum of positions, Matthew Gibney has argued that people have obligations that are both “special” (that is, toward their families and communities) and “general” (in other words, toward humanity). Drawing upon the work of Thomas Nagel and Samuel Scheffler, Gibney argues that we need to understand that in practice people value their special obligations more than their general ones. The “humanitarian principle” supported by Gibney requires that we should prioritize the welfare of the most vulnerable arriving at our territory insofar as the cost is comparatively low.[7. Matthew Gibney, The Ethics and Politics of Asylum: Liberal Democracy and the Response to Refugees (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).]

The current situation—in which many countries argue that they are “overwhelmed” and that the cost to their citizens of hosting refugees is relatively high—leaves open the question of the extent of this obligation. Are the 1.2 million refugees in Lebanon, a small country with a population of just over 4 million, too many? Are the few hundred thousand asylum seekers that Europe has taken in this year, who in theory could be divided among twenty-eight European Union member states, too many? What criteria would one need to use to determine what a “fair share” of refugees means for a given state?

Other theorists extend the argument beyond the humanitarian principle, arguing that the source of moral obligation toward distant strangers comes from the reality of our interconnected world. Seyla Benhabib, for instance, has argued that we are no longer simply part of isolated national communities, and that our moral obligations extend by virtue of our transnational interactions. The existence of a global society means that when other people suffer in the world, we are complicit in that suffering.[8. Seyla Benhabib, The Rights of Others (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).] Conflicts in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya, for instance, have been affected in various ways by the foreign policy decisions of the United States and many European powers. Thomas Pogge, for one, highlights some of those interconnections as a basis on which we can think about claims to global justice.[9. Thomas Pogge, World Poverty and Human Rights (Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Press, 2002).]

Interests

Refugee protection is not important just for humanitarian reasons. It is also crucial for global stability. As Emma Haddad has recognized, one of the inevitable consequences of the international state system is that sometimes it malfunctions. When states fail in their duty to protect the fundamental rights of their own citizens, people are forced to leave those countries, whether temporarily or permanently.[10. Emma Haddad, The Refugee in International Society (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008).] When they do so, it is in the interests of international security that they have somewhere safe to go. States collectively benefit from the availability of refugee protection, which can be considered, to some extent, to be a global public good.[11. Astri Suhrke, “Burden-Sharing during Refugee Emergencies: The Logic of Collective versus National Action,” Journal of Refugee Studies 11, no. 4 (1998), pp. 396–415.] When provided, it offers nonexcludable and nonrivalrous benefits to all states, irrespective of who contributes. Those benefits are, first, the security of reintegrating people into the state system and, second, human rights—the guarantee that people have their basic needs met somewhere.

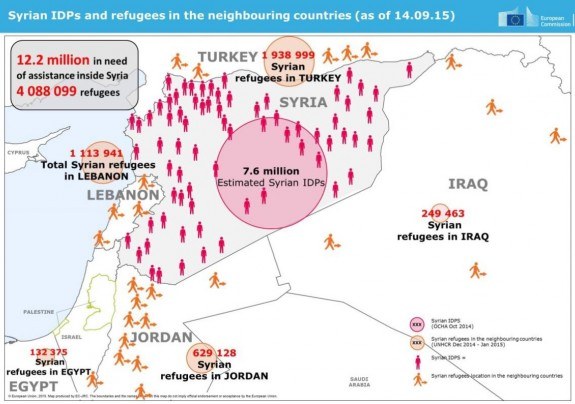

Syrian refugees and internally displaced persons. (Courtesy: European Commission)

Syrian refugees and internally displaced persons. (Courtesy: European Commission)

The challenge, though, is that typically the taking in of refugees is perceived by states as imposing economic, social, and political costs. Thus, acting in isolation, states often seek to free ride on the provision of refugee protection by other governments, and have strong incentives to engage in burden-shifting. That is one of the reasons international refugee law exists: to create a set of norms that obligates governments to a reciprocal commitment to support refugees. In that sense, when a state provides protection it is helping maintain the global refugee regime—the architecture of reciprocal support that confers a set of global public goods. The danger, of course, is that when countries fail to reciprocally commit to asylum or burden-sharing, this in turn threatens the edifice of the global refugee regime.[12. Betts, Protection by Persuasion.]

A lot of the normative analysis proceeds on the assumption that refugees impose a cost. But this is actually an empirical question, and the assumption can be challenged. In the limited research that exists on the economic contributions of refugees, there is evidence to suggest that with the right policies, refugees can make a contribution to national development and serve as a benefit to host governments and populations. Uganda, for example, has adopted the relatively enlightened “Self-Reliance Strategy,” which allows refugees the right to work and freedom of movement. In our research on the Ugandan case, we have been able to show the positive effects of this policy on the country’s economy and society. In Kampala, 21 percent of refugees employ others in their businesses, and of these, 40 percent of the employees are Ugandan nationals. In other words, refugees can create jobs for host countries.[13. Alexander Betts, Louise Bloom, Josiah Kaplan, and Naohiko Omata, Refugee Economies: Rethinking Popular Assumptions (Oxford: Humanitarian Innovation Project, 2014).] If the cost or benefit of refugees is the result of our polices rather than the innate capacity of refugees themselves, then this has implications for our normative analysis.

Values

Harvard philosopher Christine Korsgaard has highlighted that one of the most fundamental sources of normativity is identity. In her work on “self-constitution,” she argues that one of the key foundations of normativity is the way in which identities are constituted over time.[14. Christine Korsgaard, Self-Constitution: Agency, Identity, and Integrity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).] If we behave in a morally good way, this in turn shapes who we become as people. Following Korsgaard, we can understand much state behavior in relation to refugees as identity-driven. In the current refugee crisis in Europe, for example, Germany has expressed significant pro-refugee values, reflective of its self-understanding as a responsible and progressive state. In opinion polls, most Germans are strongly in favor of taking in refugees, and in August 2015 Chancellor Angela Merkel announced that the country could take up to 800,000 Syrian refugees in one year, adding that “Germany is a strong country and it will cope.”

Refugees in Budapest, Hungary. (Courtesy: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies/Creative Commons)

Refugees in Budapest, Hungary. (Courtesy: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies/Creative Commons)

Identity and values sometimes privilege taking refugees from particular countries in particular contexts, and they can also underpin exclusionary policies. During the cold war, granting refugee status in the West was seen as a way of implicitly condemning the values of Eastern Bloc countries and supporting Western capitalism. With the current influx of refugees in Europe, the Visigrád states—Hungary, Slovakia, Czech Republic, and Poland—have expressed a strong preference for taking Christian refugees. In other parts of the world, an important source of the commitment to take refugees is the Islamic value of protecting “guests.” Even though many countries in the Middle East are not signatories to international refugee conventions, they nevertheless support refugee protection based on a set of religious and historical values.

WHO TO PROTECT?

The definition of a “refugee” was created at a particular juncture of history, and in a particular geographical context: post–Second World War Europe. The definition of “people fleeing a well-founded fear of persecution” was a product of that era. Today there are new drivers of cross-border displacement, including environmental change, state fragility, and food insecurity. Many of these fall outside the framework of the Refugee Convention. This poses a question of who today has a just claim to asylum. Many authors suggest that persecution is a special case and justifies the privileged status of “refugee.” For others, the existing conception of “refugee” creates an ethically arbitrary barrier, excluding others with equally valid moral claims to protection. How do we sort out these distinctions? We can approach this issue in terms of whether persecution is a special case; whether a broader category of what might be called “survival migrants” also has a case for asylum; and whether in the contemporary world it still makes sense to even distinguish “migrant” categories.

Matthew Price offers one of the strongest defenses of persecution as a special case that creates a particular justification for asylum. While he suggests there may be grounds for granting temporary protection to people fleeing other forms of humanitarian crisis, he regards asylum to be, by definition, a pathway to permanent citizenship elsewhere.[15. Matthew Price, Rethinking Asylum: History, Purpose, and Limits (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009).] The concept of asylum, however, can be understood not necessarily as a path to citizenship but rather simply as a right to access territory, whether on a temporary or permanent basis. Seen that way, it is hard to deny that other people fleeing serious human rights violations and deprivations would also have a similar moral claim to cross an international border. Jean-François Durieux has supported this position, suggesting that there are different asylum “paradigms,” including “admission” for people fleeing persecution and “rescue” for those fleeing disaster.[16. Jean-François Durieux, “Three Asylum Paradigms,” International Journal on Minority and Group Rights 20, no. 2 (2013), pp. 147–77.] For Durieux, persecution is distinctive for two reasons: it leaves no alternative route for protection and it often enables states to admit people based on affinity with their plight, given the individualized nature of persecution. Like Price, Durieux suggests that war or natural disaster should trigger alternative forms of support, such as humanitarian aid or temporary refuge.

Internally displaced people, North Darfur, Sudan. (Courtesy: United Nations Photo/Creative Commons)

Internally displaced people, North Darfur, Sudan. (Courtesy: United Nations Photo/Creative Commons)

James Hathaway has also argued that refugees represent a distinct case: among forced migrants, they are the most deserving of the deserving.[17. James Hathaway, “Is Refugee Status Really Elitist? An Answer to the Ethical Challenge,” in Jean-Yves Carlier and Dirk Vanheule, eds., Europe and Refugees: A Challenge? (The Hague: Kluwer Law International, 1997); and James Hathaway, “Forced Migration Studies: Could We Agree Just to ‘Date’?” Journal of Refugee Studies 20, no. 3 (2007), pp. 349–69.] Fleeing their own government, they are the least likely to be in a situation in which they can seek effective redress within their own state. In addition, he argues that broadening the category to include other categories of forced migration risks undermining the availability of protection for (“true”) refugees. Others, like Gibney, find the idea that there is a clear line between refugees fleeing persecution and other forced migrants unpersuasive. According to Gibney, “these attempts fail to establish a clear, crisp, and credible dividing line between these groups. This does not mean that there are no differences at all, it is simply these differences are relatively minor, not intrinsic, and not of great moral significance.”[18. Matthew Gibney, “Should We Privilege Refugees?” Paper Presented at Refugee Studies Centre’s 30th Anniversary Conference on Global Refugee Policy, Oxford University, December 6, 2013.]

I have argued that a broader category of people is deserving of the right to seek asylum, a group that I call “survival migrants.”[19. Alexander Betts, Survival Migration: Failed Governance and the Crisis of Displacement (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013).] I define survival migrants as people who are outside their country of origin as a result of their country’s inability to ensure their most fundamental human rights. The group includes the institutional category of refugees, but is much broader. It encompasses those fleeing not only civil and political rights violations but also very serious socioeconomic rights deprivations. The moral basis of this argument builds upon Henry Shue’s notion of “basic rights”—rights without which it is impossible to enjoy any other right. For Shue, there are three basic rights: basic liberty, basic security, and basic subsistence.[20. Henry Shue, Basic Rights: Subsistence, Affluence, and U.S. Foreign Policy (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1980).] While the existing refugee definition ensures protection for people fleeing many deprivations of basic liberty and basic security, it does nothing to protect people fleeing the absence of basic subsistence. From a basic rights perspective, this is an arbitrary distinction.[21. Andrew Shacknove, “Who is a Refugee?” Ethics 95, no. 2 (1985), pp. 274–84.]

Take the case of Zimbabwe. Between 2003 and 2009, up to 2 million Zimbabweans fled to neighboring South Africa, driven out by deep socioeconomic rights deprivations resulting from hyperinflation, poor planning, drought, and the collapse of the national economy under President Robert Mugabe. These people were not fleeing the political situation so much as the economic consequences of the underlying political situation. As a result, most were not recognized by South Africa as refugees. Indeed, at the peak of the crisis South Africa had a refugee recognition rate of less than 10 percent. According to the government’s own statistics, in 2007 and 2008 it deported around 300,000 Zimbabweans each year. The outcome was clearly unjust, but it reflected the government’s use of the 1951 Convention definition of a refugee, which excluded most Zimbabweans.

UNHCR refugee camp, Za'atari, Jordan. (Courtesy: DFID - UK Department for International Development/Creative Commons)

UNHCR refugee camp, Za'atari, Jordan. (Courtesy: DFID - UK Department for International Development/Creative Commons)

The question of who to protect has implications for how to think about the important distinction between “refugee” and “migrant.” At the outset of the crisis in Europe, most commentators described it as a “migrant crisis.” This in turn led to a backlash as others suggested that it was actually a “refugee crisis.” Some media outlets such as Al Jazeera even announced that they would stop using the word “migrant.” The implicit argument was that because refugees had a particular moral claim, we should more appropriately describe the group as “refugees.” Indeed, while the majority crossing were from refugee-producing countries such as Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, and Eritrea, it was not clear that all of them would fit the definition of refugee under the 1951 Convention. In response, a number of commentators such as Jørgen Carling have argued that abandoning the word “migrant” would also entail risks, including the stigmatizing of other migrants. In fact, as he has pointed out, it is important that we recognize that all migrants have human rights.[22. Jørgen Carling, Border Criminologies Blog, September 23, 2015, “Refugees Are also Migrants. All Migrants Matter," available at: www. bordercriminologies.law.ox.ac.uk/refugees-are-also-migrants/.]

Finally, it should be mentioned that the distinctions among immigration categories, and the privileging of some over others, are premised upon a Westphalian state model, which relies upon an underlying assumption that people belong in particular states. Yet with growing transnationalism, what political community means and what it can become is an open question. Political theory in general has only just begun to consider how we might reconceive political community or understand it more broadly than in simple Westphalian terms. For many people today, one’s primary source of entitlements and opportunities comes from inclusion within, or exclusion from, the global economy—not from the behavior or protections afforded by a particular state.

HOW TO PROTECT?

The final question relates to the content of protection. What should be provided to refugees, where, and by whom? The traditional assumption is that most of the responsibility should be borne by neighboring countries. However, this “accident of geography” places the overwhelming burden on countries that often have the least capacity to absorb refugees. Indeed, 86 percent of the world’s refugees are in developing regions.[23. UNHCR, Global Trends Report: Forced Displacement in 2014, June 18, 2015.] Over a third of these refugees are hosted in camps, some are in open settlements, and over half are in urban areas, with long-term humanitarian assistance provided by state and other donor funding, such as through various UN agencies. As protection space diminishes for refugees around the world and the political climate becomes less auspicious, there is a greater need for creative thinking about how we protect threatened populations.

Who Should Host?

Where, then, should refugees be offered protection? As noted above, the existing institutional framework implicitly confers greater responsibility to those who are near than those that are far; the principle of asylum is strongly institutionalized, while burden-sharing is largely discretionary. From a deontological perspective, proximity can be justified based on an “acts versus omissions” distinction. To use force to repel those who arrive at our borders may render us morally complicit in those people’s fate. But from a consequentialist perspective the acts versus omissions distinction dissolves. To fail to assist those in need, no matter how far away, may be just as morally problematic as expelling those at our borders.

We can see how this proximity versus distance debate plays out in contemporary refugee politics. Many countries actively seek to portray refugees who are distant and remain in their regions of origin as “worthy,” and those who move spontaneously across borders as less so. This has been the official stance of Australia, which has sought to limit arrival by boat while supporting the resettlement of asylum-seekers through UNHCR. Many other countries are seeking to emulate this model; the United Kingdom, for example, is seeking to “break the connection between spontaneous arrival in Europe and access to protection in the U.K.”[22. This is a paraphrasing of the logic outlined in David Cameron’s announcement to House of Commons that the United Kingdom would resettle 20,000 Syrian refugees, but only from camps in the region, September 7, 2015.] The logic offered for this type of policy is that it makes little difference where refugees are protected. If protection “in the region of origin” can be provided, that removes the need for onward movement to other parts of the world. Holding everything else constant, there may be normative validity to this argument. However, it is an empirical question whether or not “protection in the region of origin” can actually function as a substitute for spontaneous arrival asylum in other, more distant states.

Empirically, there is some evidence to suggest that when industrialized states close their borders and instead seek to support refugees in their first country of asylum in the developing world, those developing countries become increasingly unwilling to continue to host refugees. Take the case of the United Kingdom, which faced a spike in asylum seekers in the early 2000s. As a potential solution, Home Secretary Jack Straw proposed that Tanzania take a number of the Somali asylum seekers who were then arriving in Britain in exchange for which the United Kingdom would provide Tanzania with financial support. The response was stark. Not only did Tanzania decline the offer but it used it as justification to increase restrictions in its own policies toward Burundian refugees.[23. Alexander Betts and James Milner, “The Externalisation of EU Asylum Policy: The Position of African States,” COMPAS Working Paper No. 36 (2006).] The implications were clear: while having an external dimension to European refugee policies is important, it cannot be understood to be a substitute for protection in Europe (or other rich democracies around the world).

Refugee processing center, Preševo, Serbia. (Courtesy: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies/Creative Commons)

Refugee processing center, Preševo, Serbia. (Courtesy: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies/Creative Commons)

Industrialized states have resorted to other methods in order to keep potential refugees outside their borders. Take the idea of transit processing centers—places where asylum seekers have their asylum claims processed extraterritorially. Australia, for example, uses Papua New Guinea and the island of Nauru to assess the claims of asylum seekers. Genuine refugees are transported to Australia, but those whose applications are declined face deportation. This idea has proved deeply problematic because of the human rights abuses perpetrated in Nauru’s detention centers and the way the policy leaves many lives in limbo. Other creative ideas are being mooted for how to rethink the political geography of asylum, including Special Economic Zones[24. Alexander Betts and Paul Collier, “Help Refugees to Help Themselves: Give Displaced Syrians Access to Labor Markets,” Foreign Affairs 94, no. 6, (November/December 2015).] and the concept of a “Refugee Nation” on territory specifically purchased or annexed to host refugees.[25. Alexander Betts, “Is Creating a New Nation for the World’s Refugees a Good Idea?” Guardian, Development Professionals Network, August 4, 2015, www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2015/aug/04/refugee-nation-migration-jason-buzi.]

What Rights Should Be Granted Refugees?

Existing humanitarian responses are, broadly speaking, well conceived for the emergency phase. Many states provide food, clothing, and shelter when refugees arrive. However, too often that emergency response continues year after year, leaving refugees in “protracted refugee situations.” At the same time, as many countries around the world struggle to meet the needs of their own citizens, the level of rights and entitlements that refugees should receive is not a simple matter to resolve, particularly if there is competition for resources with citizens of the host state. One potential solution would be for richer countries to provide development assistance that would support host-state nationals and refugees at an equal level of opportunity and autonomy. Instead of being an inevitable “burden,” the presence of refugees might thereby bring benefits to the host state.

In developed countries, too, there is a debate about the rights and protections refugees should receive. For example, the resettling of refugees in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark is very costly because refugees there are entitled to generous social security benefits. In Norway, for instance, a debate emerged in 2015 about whether to allocate funds to resettle a finite number of refugees from camps to Norway, or whether to allocate that money to support the majority of refugees in their region of origin. Eventually, the country decided to provide resettlement to 8,500 Syrian refugees, but the total cost was well in excess of the country’s total annual humanitarian aid budget.

A related issue is the duration of refugee protection. In certain contexts, the idea of temporary protection has been used. During the Kosovo crisis, the EU countries participated in a wider humanitarian evacuation program for Macedonia, giving Kosovar Albanians the right to settle temporarily in EU countries until the situation in Kosovo abated. Similarly, in 1995 the United States used temporary protection visas to allow people who were fleeing a volcanic eruption in Montserrat the ability to remain in the United States until they were able to return home. On one hand, this is a way of potentially making refugee protection sustainable in the long run. Some argue, however, that refugees acquire rights over time, which necessitates some kind of pathway to naturalization and ultimately citizenship.[26. Carens, The Ethics of Immigration.]

Who Is Responsible?

States have the primary responsibility for the human rights of their own citizens. When that social contract fails, other states and the international community are expected to stand in and provide surrogate protection. Protection, thus, is a duty of states. Likewise, the three main durable solutions—resettlement, repatriation, and local integration—are all about reintegrating refugees into a state. Increasingly, however, the private sector, including business, is playing a role. Recently, the IKEA Foundation gave the largest private sector grant in the history of the United Nations to UNHCR, donating €110 million, including to support the development of a “Refugee Housing Unit” to ensure sustainable shelter for refugees. Other multinational corporations, from Hewlett-Packard to UPS, are increasingly engaging with the work of UNHCR. However, while business is an increasingly important humanitarian actor, its role comes with risks. Many businesses are well-meaning, but their motives and modes of engagement with refugees vary considerably. Motives for engagement include philanthropy, corporate social responsibility, innovation, access to labor, and interventions in the supply chain; meanwhile, some companies engage on the basis of the profit motive, and others for social enterprise. It would only take one case of serious exploitation to discredit the potential role of business and undermine its potential contribution to refugee protection. Today, though, there are no established ethical or normative principles to guide private sector engagement with the refugee regime. There is an urgent need for such standards.

THE FUTURE OF THE REFUGEE REGIME

As I stated at the beginning of this essay, the refugee regime is at a crossroads. Created in the aftermath of the Second World War, the regime was a product of its time. Since then, international society has evolved. The distribution of power in the international system has changed, as has the nature of displacement. As asylum and immigration have become more politicized, so too has the protection space available to refugees diminished.

Brandenburg Gate, Berlin, Germany. (Courtesy: Leif Hinrichsen/Creative Commons)

Brandenburg Gate, Berlin, Germany. (Courtesy: Leif Hinrichsen/Creative Commons)

The issues of who, why, and how to protect refugees pose a series of normative challenges that can only be addressed by recognizing the dynamic nature of refugee protection today. Old assumptions no longer apply. Refugees are not an inevitable cost on host states; they can also be a socioeconomic benefit. States are no longer the only protection actors; markets also matter for the outcomes for refugees. The numbers and drivers of displacement are multiplying. These dynamics lead to a series of choices, and our choices are not exogenous to the dynamics that shape the normative questions.

Our answers have implications for institutional design. The Refugee Convention remains an important guiding source of norms. To renegotiate it today would be almost politically impossible; indeed, it would likely result in a worse agreement than was arrived at in 1951. Furthermore, UNHCR’s role has changed dramatically since its creation. Today it protects not only refugees but also internally displaced persons, victims of natural disaster, and stateless persons. It provides emergency relief in crisis situations, directs care and assistance to refugees, and supports them with legal advice. There is very little question that these structures should remain in place. The real questions are: How we can adapt and, where necessary, build upon this institutional order? How can we better persuade states and their societies to meet the needs of refugees? How can they adapt to be more inclusive of the people they protect? What should be provided to refugees and where should it be provided? And, finally, who has the responsibility to do so? The answers to these crucial questions will shape the future of the global refugee regime.

More in this issue

Winter 2015 (29.4) • Review Essay

Children's Rights as Human Rights

Fundamental state failures—to recognize and act in children’s best interest; to afford them the right to be heard; and to respect, protect, and ...

Winter 2015 (29.4) • Review Essay

Justice for All: The Promise of Democracy in the Global Age

For Carol Gould, to make democracy fulfill its potential, it has to be transformed from its static and formal state to a more engaged, ...

Winter 2015 (29.4) • Essay

The Rise of China: Continuity or Change in the Global Governance of Development

Exercising its vast material power, China is rapidly becoming a top lender in the bilateral field, and it is asserting its alternative ideas on aid ...